When I was growing up in Detroit in the 1950s and 1960s, there were 232 bars in my grandma’s neighborhood, a mainly Polish area in the city’s sixth police precinct. It’s no wonder that a river of booze ran through my family and the community.

When I rode my pink Schwinn bike through the neighborhood on the way to get an ice cream at Benny Skiba’s market on McGraw, it was not unusual to see grizzled old men passed out drunk in the alleys and the empty fields in the middle of the day.

The kids I played with were not afraid of the derelicts, since they never bothered us.

They were as common as the statues of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the front yards of many Polish homes and the hollyhocks that grew by the freeway.

My maternal grandparents ran a little bar called the Rose Café on Michigan Avenue that was a favorite of Cadillac and Chrysler factory workers, and I became comfortable in a saloon at an early age.

The bar felt like a safe, family setting, with plants in the window and an endless supply of Orange Crush pop for the kids.

Strangely, my paternal Grandpa Franciszek Pyzik, a Polish immigrant who lived in the same neighborhood and worked as an unskilled laborer at the Ford Rouge Plant foundry, never set foot in the Rose Café. At least, my grandmother never recalled seeing him – and she kept a mental list of all the patrons.

Grandpa Frank arrived at Ellis Island from Hamburg, Germany on the S.S. Pennsylvania on December 16, 1910.

According to the ship’s manifest, he planned to stay with his brother Wojciech at 48 Goldner Street on Detroit’s west side. Eventually, he married Tekla Matlock, another Polish immigrant, and they had nine children.

After getting a job at Ford, he spent his modest factory paychecks buying round after round for his “friends” and not taking the money home to his family.

My dad remembers a poverty-stricken childhood because of this, but happy times, too. One picture of him with some of his siblings reminds me of the old TV show “The Little Rascals.”

My enduring memory of the man I call my “lost grandpa” is that he said just a single word to me in the 10 years that I knew him. Like my Grandma Rose, I kept mental lists, too.

I’ve been forced to piece together Grandpa Frank’s life through yellowed scrapbooks, bits of family lore and Detroit history books.

I’ve read that alcoholism was a major problem for Detroit factory workers and that the “immigrant saloon” was considered the greatest obstacle to uplifting and “Americanizing” laborers.

The Detroit city council even passed a bill in 1907 prohibiting new saloons near factories in a bid to improve social conditions, stem the tide of “demon drink,” and raise moral standards.

Still, there were dozens of them within walking distance of the auto plants. You really couldn’t walk a block without passing a tiny family-run bar in my grandparents’ neighborhood or in nearby Hamtramck, a Polish enclave within Detroit.

Incredibly, more than a few of the 300 bars within the two-square-mile radius of Hamtramck at the time were tucked in between the houses.

In the sixth precinct, an area of roughly 12 miles bounded by Wyoming, Tireman, John Kronk and 24th Street, it was not unusual to find a bar on the corner of every side street, often bearing the owners’ name –Rudy or Carmen– or with a cheerful-sounding moniker, such as the Tip-Top Bar.

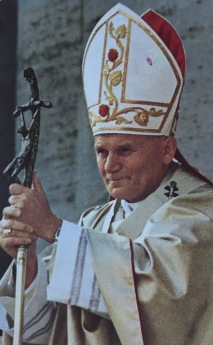

My grandmother ran a respectable saloon, cutting off the booze long before anyone could fall off a barstool. There were always two framed photos on the wall, one of the pope and the other of the president, even if he happened to be a dreaded Republican. Authority was respected.

Grandpa Frank probably drank at many of the area’s blind pigs, after-hours drinking establishments that were often raided by the cops. The pressure on him to make a smooth transition to American life and to succeed as a new Ford worker would have been nearly unbearable.

The Rouge foundry alone must have sounded like the Tower of Babel. Workers there spoke 22 different languages by the time he got his job.

Paranoia was part of the job description, too.

Ford set up a “Sociological Department” with 100 investigators to check up on laborers in their off-hours. The book Working Detroit: The Making of a Union Town notes that 80 men were taken off Ford’s “Honor Roll” in 1917 for such infractions as “Polish wedding, drunk” and “crap game while on duty.”

Even with the constant scrutiny by the boss, Detroit autoworkers would take the streetcar to work and then stop at their local bar before heading home in the days before television. Many bars were the bedrock of the community, along with the Catholic churches – an unlikely pairing, looking back.

Blue-collar workers cashed their paychecks at the bars and joined clubs sponsored by bar owners. The Rose Café sponsored the “Lucky Rose Club,” and held events at the bar to help needy families.

The Polish bars were designed to give immigrant factory workers a feeling of home. An advertisement for Skrzycki’s Bar at 6162 Michigan Avenue from 1939 offers “community singing 7 nights a week.” Michael’s Bar at 5649 Martin served “home-cooked meals” with a fish fry every Friday.

Workers were loyal to their bar – and their Catholic church.

You were known by which church you attended – St. Cunegunda, St. Andrew or St. Stephen – and your neighborhood bar. People knew which pew was theirs in church and which barstool was reserved for them. Ritual was not just reserved for religion.

My dad grew up in the neighborhood and walked the beat there as a rookie cop in the late 1940s and knew almost every bartender – and drunk – on a first-name basis.

To this day, at age 93, he can recite the number of bars in the sixth precinct and many of their names.

After he returned home from World War II and Navy duty, he and his brothers would often retrieve their passed-out father from a local potato field or driveway after a night of binge drinking.

My father told me he could never bring himself to sift through the old police records at headquarters when he became a lieutenant in the Vice Bureau to determine just how many times his father was jailed at DeHoCo, shorthand for the Detroit House of Corrections.

The concept of a family “intervention” for someone like my Grandpa Frank, who was said to be a phenomenal fiddler when he was young, was unheard of.

In fact, when my family would visit him – he lived for a time with my Aunt Bernice on Proctor – my dad always presented him with a pint of whiskey in a brown paper bag.

Grandpa’s brilliant turquoise eyes would gleam with approval, but he rarely said anything to anyone. He was always on the front porch, staring out into space.

I have just a couple of photos of him, including one where he’s standing next to my mother on her wedding day. He’s in a new suit that his kids bought for him for the occasion. He looks clean and happy. My mother said he got tipsy at the reception and somebody had to take him home.

When he was dying in a run-down nursing home that smelled of urine on East Grand Boulevard in Detroit, my father took me to visit him. I was a shy fifth-grader. When he saw me, he sat up in bed and reached out to me.

“Tillie!” he said, smiling. He had mistaken me for his wife Tekla, who had died decades earlier.

Since then, I’ve struggled to figure out what he means to my life and why he stumbled.

Did he slide into alcoholism when his nine-year-old daughter Stella died after a botched tonsillectomy at Detroit Receiving Hospital, the public hospital for indigent families?

Was he unable to cope with his wife’s chronic heart disease, frequent hospitalizations and premature death that left him alone with a large brood?

Was he ruined by job loss during the Great Depression?

Why did city and state officials allow so many liquor licenses in Detroit?

Like Grandpa Frank, I do some porch sitting with my granddaughter today and recall the silence on Proctor as Grandpa Frank sipped his whiskey. I vow that my little Eleanor will remember thousands of words from me, not just one.

Leave a comment